The Opportunity

Many African countries are in a dire public finance situation with an accelerated build-up of government debt and limited domestic resource mobilisation options. According to the OECD Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2023 the gap to reach the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in developing countries increased by 56% after the outbreak of COVID-19, totalling USD 3.9 trillion in 2020. However, it would take less than 1% of global finance to fill this gap.

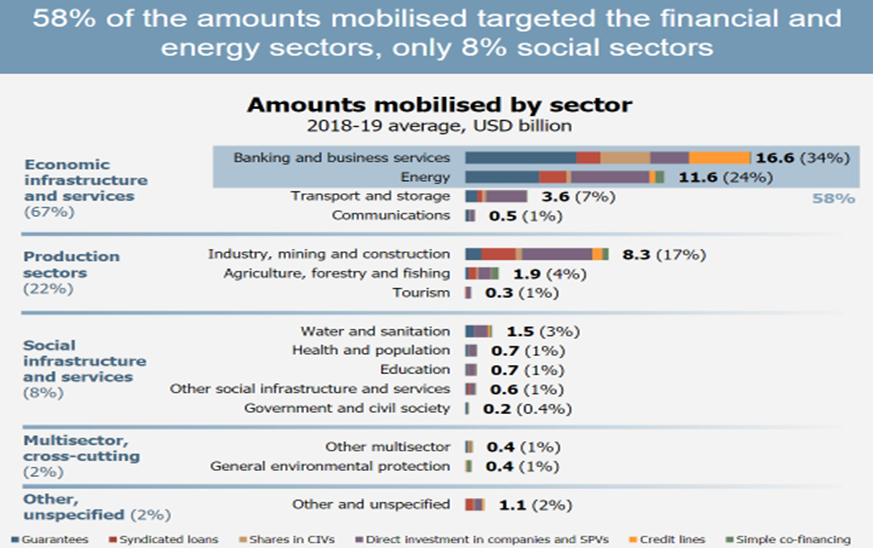

An unexpected side effect of the coronavirus pandemic has seen the rise of impact investment in the African PE space which has the added benefit of positively impacting the lives of African people as well as creating a return on investment. According to the Global Impact Investing Network 2020 survey, almost half of global impact investment capital goes to the African continent. While majority of the investments are targeted at the fintech space, there is a growing support for other critical interventions in clean energy, transport and agritech among others.

With so many demands on the limited fiscal space of many African governments, the opportunities presented by international private finance offer a viable avenue to enhance investment into critical sectors of the economy in order for African countries to achieve their sustainable development goals. This article focuses on identifying potential tax obstacles which may limit expansion of private equity investments in Africa and identify best practices globally that can assist it to expand its share of pool of international private finance.

There is an immense opportunity within Africa for a dynamic private equity industry that is capable of providing early-stage equity financing to Africa’s most innovative high-growth small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as well as creating a supportive regulatory environment to support a robust exit secondary market for private investors. SMEs and businesses backed by financial and technical support can generate economic growth, create new jobs for Africa’s burgeoning and highly entrepreneurial youth and contribute to the design and use of new knowledge and technology which will drive African economic growth for the foreseeable future. PE could also make a greater contribution to Africa’s economy if the tax environment across Africa took better account of the industry’s specific concerns and funds were incentivised to increase investments across Africa in order to achieve economies of scale that can impact the development finance paradigm.

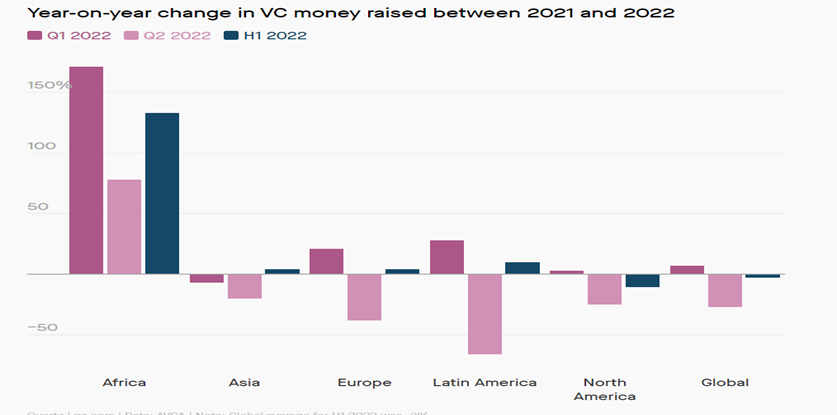

The Institute of International Finance (2020) projected that net inflows of portfolio investment and other investment to emerging markets in 2020 could drop by 80% and 123%, respectively, compared to 2019 levels. However, Africa has bucked this adverse trend with Private equity funds (PEFs) increasingly turning to emerging markets in Africa for levels of growth that were unattainable elsewhere. This is a huge opportunity for Africa to create a win-win scenario for both private investors and their own economies. According to an AVCA 2022 report between January and June 2022, no other region even came close to matching the continent’s funding growth.

AVCA’s report tallies deals for the first six months of 2022, showing that $3.5 billion was raised by 300 unique companies in more than 440 deals. This is barely 1% of global VC funding within the period, a reminder that Africa still gets the bare minimum share of the world’s start-up funding.

The reality is that while external private flows from developed countries remain volatile and dependent on low interest rates in advanced economies, there remains a huge opportunity for Africa to increasingly harness this source of development financing by removing any conceivable barriers and incentivising growth of private investments through concrete fiscal measures.

The Tax Challenges

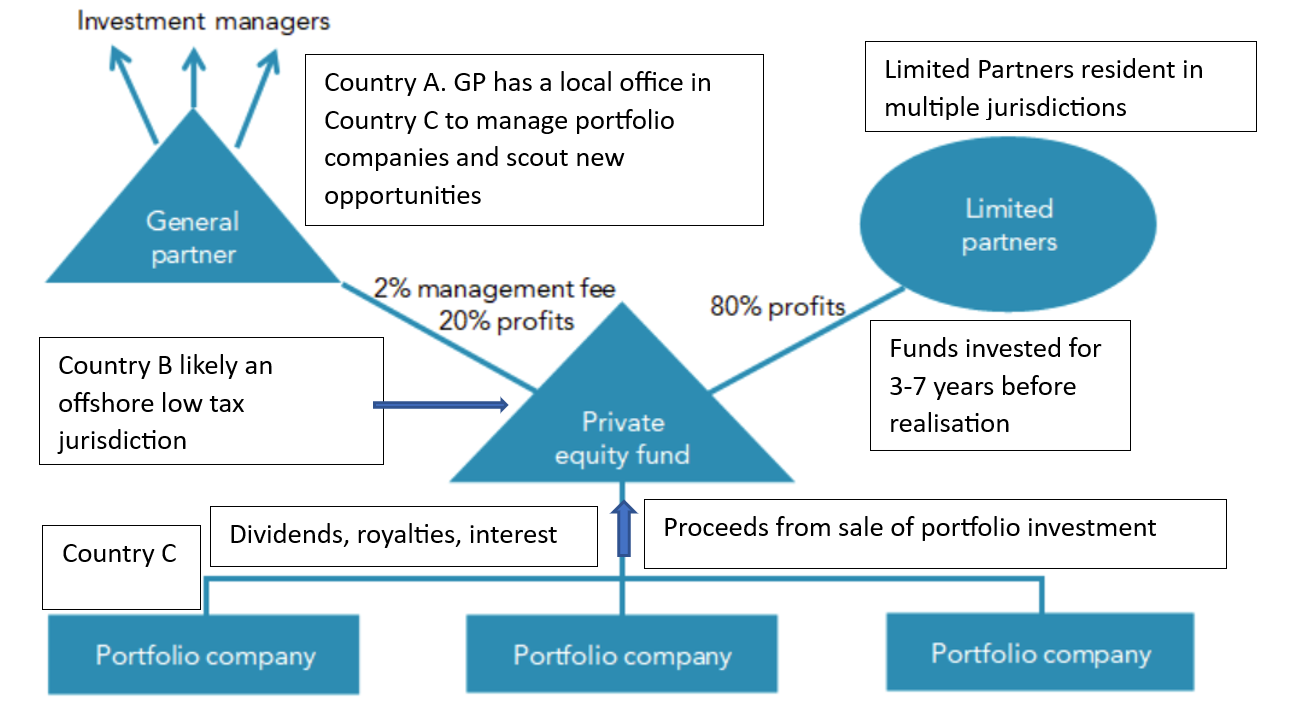

A typical PEF would be structured as below. The tax challenges arise from the fact of several cross border financial transactions all of which carry a tax implication depending on the applicable rules in each country. The tax rules are not always aligned, and which has a potentially damaging impact on the investment climate due to the double taxation effect.

To overcome some of these challenges most PEFs with a focus on Africa tend to be domiciled in tax favourable offshore countries, with Mauritius being a key jurisdiction for a fund’s domicile due to an established track record, investor safeguards, deal structuring and tax flexibility. Varied types of business structures for this purpose include global business companies, limited partnerships, protected cell companies (PCC) and trusts. The effect of these offshore investment structures has been to mitigate against any incidence of tax liability in the portfolio companies jurisdiction including corporation taxes based on trading income from purchase and sale of business, capital gains taxes, stamp duty and VAT which are often associated with having a taxable presence in those jurisdictions.

However, while these offshore structures offer a lot of tax sheltering opportunities which have previously proved quite effective, major changes to the international tax landscape particularly through the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project are increasingly posing a risk to these structuring arrangements. Tax administrations are increasingly enhancing their focus on addressing BEPS risks arising from cross border transactions and horning in on private investment fund activities. In Kenya we have increasingly observed a trend towards attempting to impute taxes based on the activities of these offshore investment funds which are already quite active within Kenya.

According to Peter Koerver Schmidt, a wide range of tax-related questions may come up with respect to the activities of PEFs. A non-exhaustive list could include issues such as taxation of capital gains, taxation of carried interest, deductibility of interest expenses and management fees, withholding taxes on interest and dividends, economic and juridical double taxation and the applicability of anti-avoidance rules. Moreover, an import issue concerns the question of whether the investment in a private equity fund may create a permanent establishment (PE) for foreign investors.

The cross-border management of PEFs risks creating a layer of taxation at the level of the management of the funds. The different tax treatment of PEFs in different countries creates further problems. While most African states have agreed bilateral double taxation conventions (DTCs) which should normally allocate taxing rights to prevent the occurrence of double taxation the often-complex commercial structures used in PEFs are not always accommodated leading to double taxation, tax treatment uncertainties and administrative obstacles.

It is also the case that most African Double Tax Treaties (DTTs) do not address treatment of PEFs. Both the OECD and UN have sought to address the issue of taxation of Collective Investment Schemes (CIVs) which constitute one of the largest categories of investors in foreign capital markets. However, there is no specific reference to measures to protect “non-CIVs” (term coined by the OECD) refer to investment funds that are similar to CIVs which are not regulated (since they only involve institutional investors such as banks, insurance companies, pension funds etc. which do not require investor protection) or because they do not hold a diversified portfolio of securities. A “non-CIV” would include, for instance, a private equity fund set up as a limited partnership in order to acquire specific assets, such as all the shares of an under-performing publicly-listed company, with the limited partners being institutional partners that provide most of the capital and the general partner being the specialized investment firm set up and manages the fund. It could also include a venture capital fund that would be similarly structured to seek private equity participations in start-up enterprises with growth potential. The UN Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters have argued that, if developing countries want to encourage portfolio investment in their territories, it would be useful to clarify whether and how tax treaties will apply to ‘non CIVs’ and/or provide domestic tax provisions that clarify tax treatment of these entities. Without such clarification, foreign investors may be reluctant to invest in a country or, if they do invest, the tax administration may have to address difficult treaty issues without a clear indication of the policy that the country has adopted in relation to foreign CIVs.

The general trend is that the tax treatment applied to PEF Managers and investments in PEFs is less favourable than that applied to public equity managers and investments in public equity such as through the stock exchange. Generally CIVs may not be entitled to treaty benefits under tax treaties because, in many cases:

- the interests in the CIV are not publicly-traded (even though these interests are widely distributed);

- these interests are held by residents of third States;

- the distributions made by the CIV are deductible payments;

- the CIV is used for investment purposes rather than for the “active conduct of a business”;

- the CIV does not meet the ownership test prescribed in most treaties;

- the CIV does not qualify as a headquarters company.

It is telling that while African Governments have issued tax and other regulatory concessions to make capital markets more attractive, there are limited fiscal regulations or incentives targeted at PEFs. Some of the incentives granted to promote development of capital markets would apply well to the private equity investments as well. For instance:

- Zero corporate tax for investee companies of real estate investment trusts (REIT) as well as the REIT that carries on investments collectively on behalf of the unit holders or shareholders.

- Tax deductibility of all investment costs for the purposes of income tax determination -All investment costs accepted as deductions against income and profits, and therefore are taken into consideration when determining profit for tax purposes.

- Stamp duty and VAT waivers on the secondary market trades.

- Capital gains tax waivers on gain realized by selling investments in the secondary market.

- Reduced withholding taxes on dividend income on distribution to beneficial shareholders.

- Tax deferral until distribution to contributors in the case of pension funds.

Questions arising from cross border investment operations include two key categories;

- Questions touching on the liability to tax of incomes generated by the investments by the Funds in the countries where the portfolio companies are bought and sold.

- Questions touching on the tax implications of having a local representative of the Investment Manager in the local jurisdiction of the portfolio companies.

Tax liability of VC Fund

An issue arises for VC funds where that the varying tax classification and tax treatment of the Funds and their investments across different jurisdictions which is a potential source of double taxation. The organization of the private equity fund as a limited partnership normally entails that the fund itself should be considered transparent for tax purposes. A tax transparent entity is an entity in respect of which the entire profits and gains are treated under the law of another jurisdiction as directly attributable to each investor in the CIV who will pay tax on its respective share of the income derived through the CIV and no tax will be payable by the CIV. The domestic tax law may also provide that CIVs shall be taxed on their income and that investors are not taxed on distributions by the CIV. In such situations no economic double taxation of the income generated by the CIV should occur, provided that both the source state and the state of residence of the investors acknowledge that the fund is transparent for tax purposes. However, juridical double taxation may occur if both the source state and the residence state consider themselves entitled to tax the income of the PEF.

We have also noted instances of the tax authorities in the jurisdiction of the portfolio company demanding taxes in instances where a PEF makes a transfer of shares from the offshore holding company. In such instances tax administrations are grappling with the question whether to treat the income as trading or investment income, which are often subject to differing tax rates.

Issues also arise whether PEFs are ‘resident persons’ capable of claiming benefits of Double Tax treaty benefits when receiving dividend interest and capital gains from the state of the portfolio company. Finally, one must also consider whether treaty-shopping and limitation of benefits concerns could arise with the use, by investors of third states, of foreign CIVs established in states with which the portfolio companies concludes treaties. Given that non-CIVs are generally not addressed in existing tax treaties and in the UN and OECD models, the antitreaty-shopping rules should be of a particular concern for non-CIVs with investors in many different countries. Countries can address this through domestic legislation to specifically exclude non-CIVs from the general treaty anti-abuse rule.

Tax implications of having a local representative of the Investment Manager in the local jurisdiction

The reality is that VC cross-border investments require a local presence (i.e. in the state of the portfolio company) to help the VC Fund Manager source new investments in those states and look after investments it has acquired there. Ideally, the activity at the local level should include full management functions (basically the capacity to make or actively contribute to investment decisions and manage the portfolio companies). However, the current tax rules on creation of a dependent agent permanent establishment are such that a PEF has to resort to restricting its activities artificially in order to avoid additional tax at the management level and this greatly reduces the effectiveness of the PEF in the portfolio state. The PEF Manager will wish to avoid this permanent establishment risk so as to prevent double taxation (i.e. to prevent taxation of the investment in the country where the investment takes place and also in the country where the investors are located).

Such double taxation can make investing in private markets uneconomic for investors. PEF Managers will usually set up separate advisory companies which analyse the local market, identify and evaluate potential investment opportunities and prepare investment proposals, with appropriate input from the PEF Manager, but do not carry out management functions. From our experience there are increasing instances where this arrangement is challenged by the tax authorities implying that the permanent establishment risk is not completely eliminated by the arrangement.

Finally, issues have arisen whether a PEF Manager bears liability for any taxes accrued by the Investment funds they manage on behalf of investors (particularly where there is clear discretionary control of the Fund by Manager). This can pose an onerous financial and legal burden for Managers especially where the proceeds have already been distributed to Fund shareholders.

To provide certainty in this area and to attract foreign investors to locally managed funds, a few countries have unilaterally clarified that they would not consider that the activities of a local fund manager would constitute a permanent establishment for foreign investors.

The Way Forward

Given the growing list of issues touching on taxation of cross border investments which have the potential to negatively impact on PEF investment activities in Africa there is urgent need for concerted action towards a more stable and certain fiscal regime for PEFs in Africa. An important first step would be for African policymakers to give proportionate tax treatment to PEFs similar to that granted to domestic collective investment schemes, low risk capital (e.g. bank deposits, bonds) and capital markets.

Investors should also be aware of these emerging risks and challenges and seek professional advice on ways of mitigating risks when dealing with any tax administration queries.

There is also need for a concerted effort to lobby African policy makers to focus on elimination of tax obstacles to cross-border investments (such as the tax treatment of dividend, interest and royalty payments, capital gains tax, cross-border losses and restructuring), and the need for co-ordinated action to eliminate economic and juridical double taxation of the profits of PEFs.

While some of the issues may be adequately addressed through double tax treaty provisions, African governments may also expressly address these concerns through domestic legislation, unilateral administrative guidance or seek mutual recognition of the classification of legal forms for tax purposes through a mutual agreement procedure between competent authorities.

The commencement of trading under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) promises to facilitate the growth of very lucrative investment opportunities for the private sector. By creating a unified single market of 1.3 billion people with a GDP of $3 trillion, the AfCFTA provides the mechanism for African countries to pursue industrialization through enhanced investments, using the continental market as a platform for learning and perfecting products to compete effectively in global markets.

The Africa Union has a role to play in promoting collective action by African policymakers towards resolving the impediments to foreign direct investments particularly in the case of collective investment schemes. Reforming tax policy in Africa to leverage additional private capital in all critical sectors could likely be the game changer strategy for the next decades in order to attain the performance markers articulated within the African Union Agenda 2063 and United Nations Agenda 2030.

Finally, for AVCA members there is need for concrete and pragmatic steps to identify the existing fiscal barriers that are hampering their appetite for investing in Africa for a more concerted action by the Association towards addressing those issues with policymakers.

Author

James Karanja